Our deceptive memory

Let’s say you and I are guests at a wedding party.

We are sitting in the same room, but may go home with completely different memories of this wedding. You experience a wonderful celebration, I experience an increasingly large run in my tights, which ruins my festive outfit and therefore spoils my party mood. There’s always something.

So while you’re having a great time, switching tables to talk, dance and party like you haven’t in a long time, I’m sitting cramped up in my seat, hiding my runny legs under the table and hoping that no one notices my mishap.

Which of us will remember this celebration better later?

No question: I will! You will go home with the better memories, but I will remember it longer because I was so annoyed (with myself).

Bad news are good news – the fact that bad news is good for business is not an invention of newspaper makers and news editors.

They simply take advantage of the fact that we are more impressed by bad news and experiences than by good ones, and to make matters worse, we remember them better.

Our good memory for bad things is a heritage that we owe to the residues of our evolution, just like the appendix and armpit hair: The fact that saber-toothed tigers are bitey and which berries should definitely not be eaten was the more important news (for survival) for our ancestors in the early history of mankind compared to the good news.

So our memory is by far not as objective and sorted as we would like it to be.

In the imagination of most people, memory is a kind of chest of drawers in the head, in which we stack our memories neatly folded and well-ordered until we need them and dig them out again. But this is not so.

The catch with the idea of “objective” and unchangeable memories is that it is not true.

Why we should sometimes not trust our memories

We pay less attention to the positive experiences in our lives, and we forget them more quickly.

That’s why the family party at which the waiter dropped the tray with the dessert, grandpa’s pants seam burst, or a rainstorm poured down on the wedding party after everyone had finally lined up for the photo remains much better in our memory than parties at which everything went smoothly.

However, how we remember and what we can retrieve from our memory depends not only on our mood at the time, but also on our state of mind at the moment when we remember: If we are in a good mood, we remember mainly nice moments and funny incidents; if, on the other hand, our mood is rather cloudy, a lot of unpleasant things suddenly pour out of our memory drawers.

So our memory is not only changeable – plastic – but also has a daily form.

An interesting experiment on how we color and weight our memories depending on our mood was conducted by Italian psychiatrist Giovanni Fava.

Fava asked some of his patients who were being treated for depression to keep a “happiness diary” of the good moments in their lives. At first, most of his patients reacted dumbfounded, because they assumed that they had no beautiful moments because of their illness.

But they had, as their happiness diaries clearly proved.

One patient, for example, reported how happy he was that his family had been so pleased to see him. However, he destroyed this happiness himself the next moment with the thought “they are only happy about the presents I brought“.

You also have to (be able to) allow positive memories.

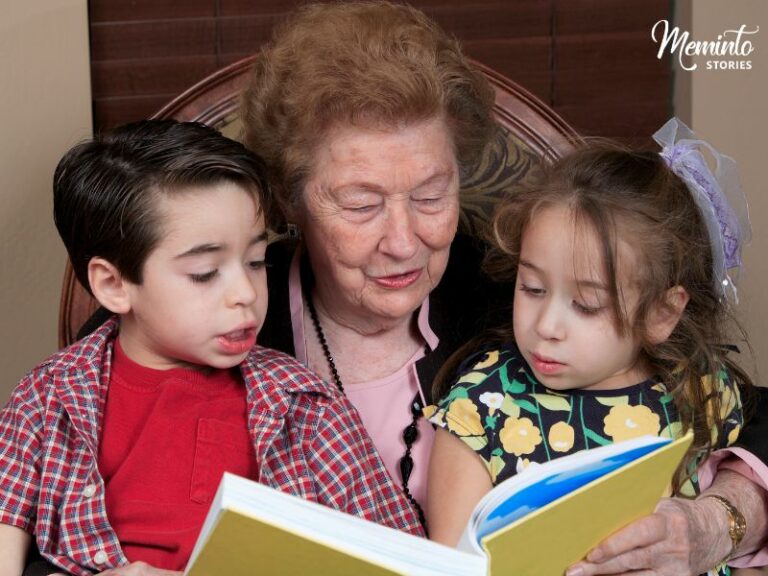

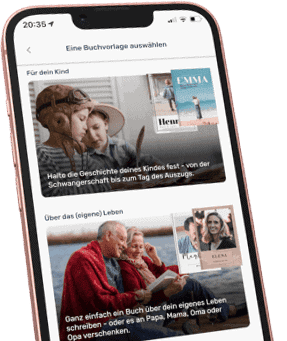

Writing Family biography: It's more fun together

Shared experiences and memories are the super glue that holds families, friendships and couples together.

We keep our memories alive for good reasons, because they bind us together even more and give us a sense of security, especially during stressful periods in life, because they remind us that we are not alone in this world.

However, as we have seen, our memories of the same experience can differ from each other because of the plasticity of our memory, which always leads to heated discussions as soon as you sit together and try to recapitulate a common experience:

“On Christmas Eve 2009, we had roast goose as usual!”

– “Nah, goose was out, so we had duck!”

– “Nonsense, we were going to cut back that year. We had sausages with potato salad!”

Feel free to put it to the test and have family, friends or other favorite people tell you about Christmas Eve 2018 or the last big family event before Corona.

You’ll be amazed at all that’s supposed to have happened that day or evening, and perhaps wonder at some point if you were even there.

However, these discrepancies in our – shared – memories are not only fuel for discussion, but can also be a wonderful hook for new wonderful experiences and memories. For example, by using them not only to tell the common story, but also to write it down.

Especially at a time when many reunions and celebrations (have to) fall through, the project “We write down our history” can bring families and friends closer together and get them talking to each other again.

The fact that we all remember one and the same event differently is not an obstacle here, but quite the opposite, part of the fun for everyone involved:

- The joint project “We write down our history” works best when everyone who wants to participate meets at regular intervals.

At the moment, of course, online, although this is also a good solution for normal times, because then even the uncle in Australia and the aunt from Wiesbaden can be there without any problems. - Because our memory is known to develop its own idea of truth, very different accounts of one and the same event will certainly make the rounds during the meetings via Zoom (or another platform).

In order to be able to clarify the question of how it really was, there will therefore be a homework assignment for everyone to “search and sort photos“. If a photo of Christmas 2009 turns up with the bowl of potato salad clearly visible in the background, the discussion should be settled and off the table. - Please remember: A handful of beautiful photos will do more for your memories (and those of your loved ones) than a thousand unsorted pictures on your cell phone or the memory chip of your camera. Therefore, take time as regularly as possible to sort through your photos, select the most beautiful ones and show them off.

- Diaries – or modern: Journals – are another source that is much more objective than our memories: What you wrote down at the time, perhaps shortly after an important event, is there in black and white and cannot be colored or changed afterwards by our elusive memory.

- Equally valuable are wedding newspapers, guest books, notebooks with quotations, but also old family recipes, anecdotes and the favorite sayings that Grandpa or Aunt Emma always gave in certain situations to the best.

You decide which topics you take up and with which people you share your project – as a couple with your best friend or in the big family circle. There will be plenty to laugh about, and sometimes maybe even to cry about. You will have a lot to talk about together, get closer to each other – and perhaps get to know your common history from a completely new perspective.

I wish you much joy in the process!

Dr. Susanne Gebert has worked as a freelance biographer and ghostwriter since 2013 and blogs about psychology, history, childhood and education at www.generationen-gespräch.de

Picture credits: Agentur für Bildbiographien Dr. Susanne Gebert